Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Circulación extratropical: Ondas de Rossby

- Fundamento

- El experimento

- english version

El Sol emite energía en forma de radiación electromagnética, calentando la Tierra. Sin embargo, la distribución del calor a lo largo de la superficie terrestre no es homogénea: las regiones ecuatoriales y tropicales reciben mucha más energía solar que las latitudes medias y las regiones polares.

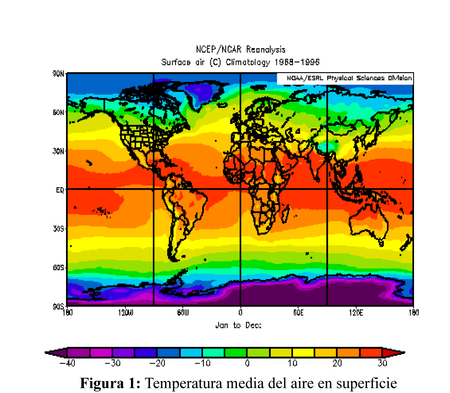

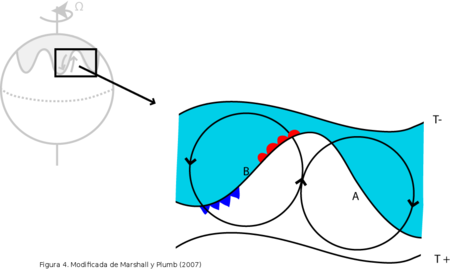

Además, la Tierra también emite radiación hacia el espacio, pero la cantidad de energía emitida por la Tierra tampoco es homogénea, ya que depende de la temperatura de la superficie. Las regiones tropicales, que están más calientes, emiten más energía que las regiones polares, que están más frías (Figura 1).

Aún así, en latitudes bajas la cantidad de energía recibida es mayor que la emitida (hay ganancia de energía), mientras que en latitudes altas la cantidad de energía emitida es mayor que la recibida (hay pérdida de energía). De este modo, si no hubiera transferencia de calor entre los trópicos y las regiones polares, los trópicos se calentarían más y más, y los polos estarían cada vez más fríos.

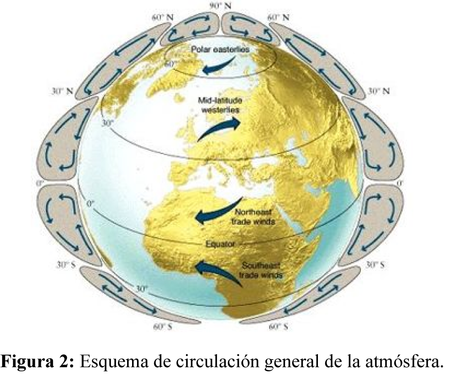

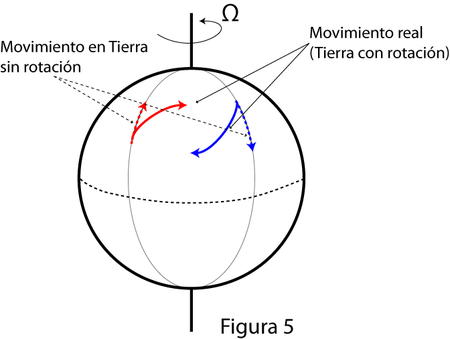

Este desequilibrio de calor latitudinal (norte-sur) es el origen de la circulación de la atmósfera y los océanos: la energía calorífica se redistribuye desde las regiones más cálidas hasta las más frías por medio de la circulación de la atmósfera (60%) y del océano (40%). La Figura 2 muestra un esquema de la circulación global de la atmósfera.

¿Cómo redistribuye la atmósfera el exceso de calor de las regiones tropicales?

En latitudes tropicales, la redistribución de energía la lleva a cabo básicamente la circulación de la célula de Hadley. Ésta consiste en ascensos del aire caliente (convección) alrededor del Ecuador, que una vez que alcanza los 10-12 km (el tope de la troposfera, puedes ver un perfil de la atmósfera estándar en el experimento de contaminación atmosférica) se dirige hacia latitudes más altas de ambos hemisferios. En 30ºN y 30ºS aproximadamente, el aire vuelve a descender hasta la superficie, viajando de nuevo hacia el Ecuador para completar la célula.

En latitudes medias, no existe una célula de circulación similar a la de Hadley que transporte energía a latitudes más altas. El transporte lo llevan a cabo fundamentalmente las ondas planetarias transitorias o de Rossby*, que son generadas por inestabilidades térmicas y/o dinámicas en el flujo del oeste propio de las latitudes medias.

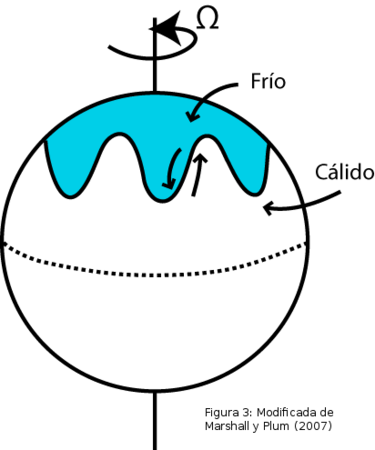

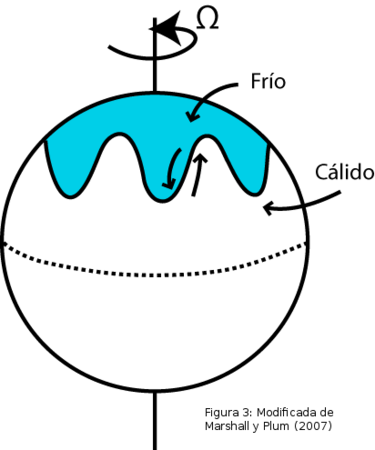

Las circulaciones con forma de onda en la troposfera media y alta de latitudes intermedias provocan un transporte neto de calor hacia latitudes más altas: los remolinos transportan aire frío hacia el ecuador y aire caliente hacia el polo, reduciendo la diferencia de temperatura entre el ecuador y los polos; el aire frío se transporta hacia el ecuador al oeste del frente, mientras que al este el aire cálido se trasporta hacia el polo (Figura 3).

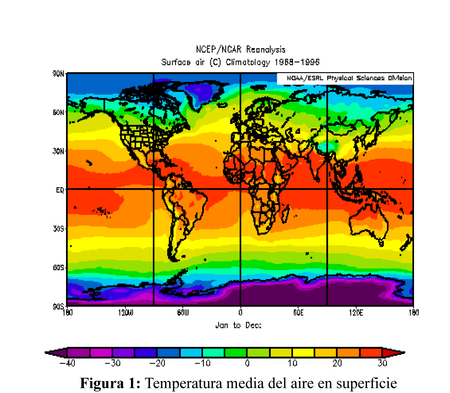

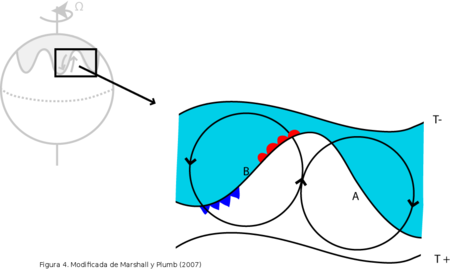

Estas onda a menudo forman remolinos cerrados, especialmente en la superficie: las borrascas y anticiclones de las que hemos oído hablar todos los días a la persona que da el tiempo en la tele (Figura 4). En esta figura la “B” indica una borrasca (ciruclación ciclónica anti-horaria y baja presión) y la “A” indica un anticiclón (circulación horaria y alta presión). Hacia los polos el aire está más frío (T-) y hacia el ecuador más caliente (T+). De esta forma se producen frentes fríos (marcados por los triángulos azules en la figura 4) y frentes cálidos (marcados por los semicírculos rojos en la figura 4).

¿Por qué se forman esas ondas?

Por la rotación de la Tierra, la circulación de la atmósfera se ve condicionada por una cosa: la conservación del momento angular. La circulación general, además de asegurar la redistribución de la energía, debe compensar el transporte de momento, por lo que la circulación atmosférica no puede ser puramente meridional, habiendo forzosamente vientos de componente paralela al ecuador. Por ejemplo, si una partícula de aire se mueve en altura hacia el este, tendrá mayor velocidad angular que un punto del suelo (inmóvil) situado a la misma latitud y, por tanto, tenderá a desplazarse hacia el sur en busca del paralelo que por su fuerza centrífuga le corresponde. Al desplazarse hacia el sur aumentará el radio de giro en la proporción conveniente para compensar la pérdida de velocidad angular necesaria para que la partícula se ajuste a la rotación de la Tierra.

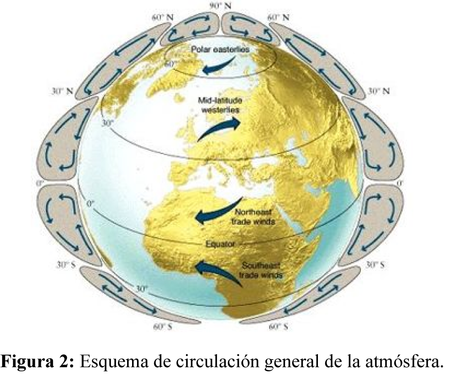

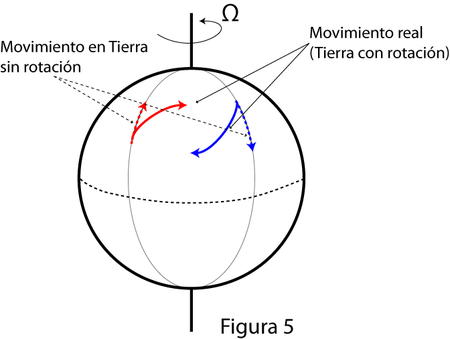

Así, en cualquier dirección en que se mueva una partícula de aire, la rotación terrestre produce sobre ella un efecto de desviación hacia la derecha en el hemisferio norte y hacia la izquierda en el hemisferio sur (figura 5). Esta fuerza desviadora se conoce como efecto Coriolis o aceleración de Coriolis.

* Se conocen como Ondas de Rossby en honor de Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby, meteorólogo estadounidense de origen sueco que explicó por primera vez los movimientos atmosféricos de gran escala basándose en la física de fluidos.

Referencia:

Marshall J. y R. A Plumb (2007): Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate Dynamics. Ed. Academic Press Inc, 344 pp.

Aqui puedes verlo en un experimento

The Sun emits electromagnetic radiation and warms up the Earth. However, the solar heating is not uniformly distributed on the terrestrial surface: equatorial and tropical regions receive much more energy than the midlatitudes and polar regions.

Additionally, Earth also emits radiation to space and this energy loss is again non-uniform because the emitted radiation depends on the surface temperature. Tropical regions, which are warmer, lose more energy than the colder polar regions (Figure 1).

Even so, low latitude regions receive overall more energy than they emit (i.e., they are subject to net warming), while high latitude regions emit more energy than they receive (i.e., they are subject to net cooling). Thus, in the absence of heat transport from the tropics to the poles by the atmosphere and oceans, the tropical regions would be warmer and the poles would be colder.

This latitudinal (north-south) energy imbalance fuels up the atmospheric and oceanic circulations, which redistribute the solar energy by transporting heat from warm to cold regions (roughly 60% of this transport is carried by the atmosphere and 40% by the ocean). Figure 2 shows a schematic of the global atmospheric circulation.

How does the atmosphere redistribute the excess tropical heating?

Over the tropical latitudes, energy is redistributed meridionally by the Hadley cell. This circulation arises as warm air rises near the Equator (convection) and moves poleward in both hemispheres at a height of about 10-12 km (the depth of the troposphere –you can check the standard atmosphere profile in the atmospheric pollution experiment). At approximately 30 degrees latitude, the air sinks down to the surface and then travels back to the Equator at surface levels closing the circulation.

There is no similar circulation cell transporting heat poleward in the midlatitudes. Over that region, heat is mainly transported by transient Rossby* waves of planetary scale, which are generated by the dynamical instability of the midlatitude westerly jet stream.

Wave circulations in the midlatitude trosposphere produce a net heat transport to higher latitudes: eddies carry cold air toward the Equator and warm air toward the Pole, reducing the Equator-to-Pole temperature difference. The cold equatorward transport occurs west of the frontal region while warmer air moves poleward on the east of the front (Figure 3).

This wavy structure often consists of closed eddies, especially at the surface: these are the cyclones and anticyclones that we are familiar with from TV weather programs (Figure 4). In this figure, “L” stands for low pressure system (cyclonic anticlockwise circulation) and “A” for anticyclone (clockwise circulation and high pressure). Air moving poleward is colder (T-) than air moving equatorward (T+), as indicated by the cold (blue triangles in Figure 4) and warm (red semicircles in Figure 4) fronts.

¿Por qué se forman esas ondas?

Angular momentum conservation poses an important constraint on atmospheric motions due to Earth rotation. As the global atmospheric circulation redistributes energy latitudinally, changes in the angular momentum of meridionally moving air parcels must be compensated by wind acceleration parallel to the Equator. For example, when an air parcel moves eastward at upper levels it rotates faster than the (fixed) surface at the same latitude and will therefore tend to move southward toward a latitude consistent with its centrifugal force. As the parcel moves southward, the distance to the axis of rotation will increase the right amount to compensate the angular velocity loss to adapt to Earth’s rotation.

Thus, when air parcels move in any direction, Earth’s rotation will deflect their trajectories to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere (Figure 5). The deflecting force is known as the Coriolis effect or the Coriolis acceleration.

* Rossby waves owe their name to Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby, the Sweedish-American meteorologist who pioneered the application of Fluid Mechanics to large scale atmospheric motions.

Referencia:

Marshall J. y R. A Plumb (2007): Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate Dynamics. Ed. Academic Press Inc, 344 pp.

Créditos:

Elaborado por:

Javier García Serrano

Proyecto de Innovación y Mejora de la Calidad Docente. Laboratorio Virtual de Meteorología y Clima (122PCD1144)

IP: Belén Rodríguez de Fonseca