Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Deshielo Polar

- Fundamento

- Diseño

- english version

Fundamento teórico

Este experimento se basa en corroborar qué efecto tendría el deshielo de los casquetes polares sobre las corrientes geostróficas. La idea surge tras leer un artículo publicado en Abril de 2013 en Scientific Americanb por Stephen C. Riser y M. Susan Lozier, profesores de oceanografía de las universidades de Washington y Duke respectivamente. En él se plantean la validez de la teoría clásica más aceptada que relaciona la corriente del Golfo con los inviernos de Europa, dado que nuevos modelos numéricos e investigaciones avalan teorías alternativas.

|

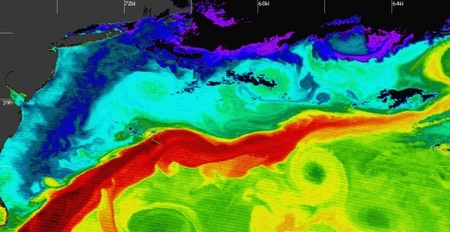

| Ilustración 1. Corriente del golfo en América. En rojo se aprecian las regiones de mayor temperatura, pasando por las amarillas, verdes, azules y violetas que son las regiones más frías. |

La teoría clásica

Se explica así: los inviernos en Europa son más suaves que los correspondientes a otras partes del globo sobre la misma latitud porque la corriente del Golfo transporta masas de agua cálidas tropicales a lo largo del océano Atlántico que, al llegar a las costas occidentales europeas, liberan su calor dejando que los vientos del oeste lo introduzcan en el continente.

|

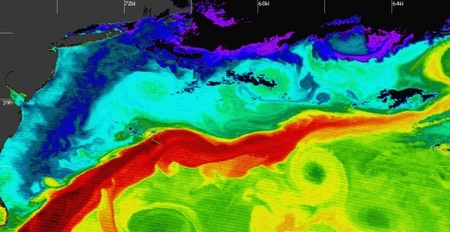

| Ilustración 2. Corriente del golfo en América. En rojo se aprecian las regiones de mayor temperatura, pasando por las amarillas, verdes, azules y violetas que son las regiones más frías. |

La teoría rival

Añade una de diferencia sutil a la teoría clásica: la corriente del Golfo sigue su camino desde América hacia Europa pero esta vez se considera a la corriente en chorro (jet-stream) la responsable de agitar las aguas generando una turbulencia sobre la superficie oceánica que resulta en la liberación de la energía almacenada. Se cree que dicha agitación resulta tanto más intensa cuanto más cerca se encuentran ambas corrientes de Europa.

|

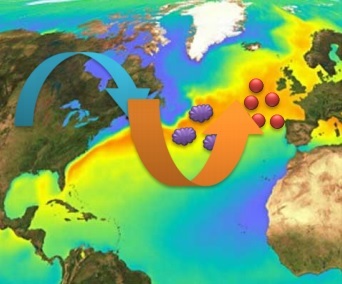

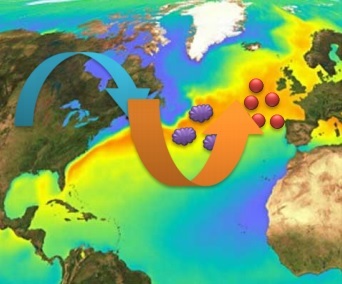

| Ilustración 3. La corriente del Golfo se abre paso hacia Europa donde la corriente en chorro (azul, vientos fríos; naranja vientos cálidos) agita la superficie oceánica (nubes moradas) y con ello libera calor en las cercanías del continente europeo. Considerables esfuerzos de la red ARGO mundial permiten corroborar este tipo de teorías mediante modelos numéricos con datos extraídos de boyas repartidas por todo el océano. |

Aunque no es la única teoría rival, sí es la más relevante.

Deshielo de los polos

Es bien sabido por los lectores que el agua dulce es menos densa que el agua salada, y por tanto, en ausencia de efectos de mezcla, esta se hundirá bajo aquella. Así ¿cómo podría afectar a la corriente del Golfo (y al resto de corrientes geostróficas en general) la fusión de los glaciares? ¿Podría repercutir en los inviernos de Europa? Eso es lo que pretendemos averiguar con este experimento.

Diseño experimental

Para conseguir reproducir la situación que tendría lugar, necesitamos colocar una fina capa de agua dulce sobre otra profunda de agua salada, representando la situación de fusión de los polos. Con un tinte seremos capaces de diferenciar ambas capas.

A su vez debemos generar una célula convectiva a través de un gradiente de temperatura vertical sobre todo el fondo de manera uniforme. Ello simulará la corriente del Golfo en la superficie oceánica (nótese que la corriente del Golfo NO es el resultado de una macro célula convectiva generada por un gradiente de temperaturas).

Para evitar la turbulencia que pudiera provocar la mezcla de ambas capas de agua, necesitamos que la recreación de las condiciones se produzca de la forma más lenta posible (o al menos de forma natural). Optamos por dejar al hielo derretirse a temperatura ambiente sobre una solución salina y calentarlo con vapor de agua hervida.

Polar Melting

Basics

This experiment aims at showing the effect of ice melting over geostrophic currents. This idea popped up after reading a paper in Scientific American by Stephen C. Riser and M. Susan Lozier, physical oceanography professors in the universities of Washington and Duke, respectively. The paper addresses the validity of the classical theory accepted that relates the Gulf Stream with winters in Europe, since new numerical models and researchers support alternative theories.

Figure 1: Gulf Stream in America. Red indicates the regions with the highest temperatures, down to yellow, green, blue and purple, that are the coldest ones.

The classical theory

It goes like this: European winters are milder than those in other regions of the Earth at the same latitude because the Gulf Stream transports wam tropical waters toward these areas that release heat when reaching the European coasts, allowing the westerly winds in the area to transport this heat toward the continent.

Figure 2: Gulf Stream in America. In red are shown the regions with highest temperature, down to yellow, green, blue and purple, that are the coldest ones.

The alternative theory

It introduces a subtle difference to the classical theory: the Gulf Stream follows its path from America toward Europe but the jet stream produces turbulent mixing of the ocean surface that releases the heat stored in the ocean. It is thought that this mixing strengthens as both currents approach Europe.

Figure 2: The Gulf Stream opens up its way toward Europe where the jet stream (blue: cold winds; orange: warm winds) stirs up the surface of the ocean (purple clouds). This releases heat close to the European continent. Important efforts of the global ARGO array allow to evaluate such theories by comparing the results of numerical models with data from buoys spread world-wide. Although this is not the only alternative theory, it is the most important one.

Ice melting at the poles

It is well known that salty water is more dense than freshwater. This, in the absence of mixing, it will sink below. How would the Gulf Stream (and the rest of the ocean currents) be affected through ice melting at the poles? Could this impact the winters in Europe. This is the question that we assess in this experiment.

Experimental Design

To reproduce the situation that would take place we need to place a thin layer of surface freshwater over a layer of salty water, thereby mimicking ice melting at the poles. A color dye allows identifying each layer.

At the same time we need to generate a convective cell through a vertical temperature gradient. This will mimic the Gulf Stream flow at the surface (note, however, that the Gulf Stream is not the result of a macroscopic convective cell generated through a temperature gradient).

To prevent turbulent mixing between the two layers we need that the process tales place as slowly as possible, or in a natural manner. To this end we allow the ice to melt at room temperature over a saline solution and warm it up with boiling water vapour.

Créditos:

María Ángeles López Cayuela y Guillermo Martín Martínez, para la asignatura de Oceanografía Física, del Máster de Meteorología.