Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Densidad del Agua del Mar

- Fundamento

- Diseño

- Experimento

- english version

La densidad es una magnitud que mide la proporción que existe entre la masa de una sustancia y el espacio que ésta ocupa, esto es, el volumen.

ρ= m / V

Para los gases (ideales), esta densidad depende de la temperatura de forma inversamente proporcional. Si se calienta un gas encerrado en un globo por ejemplo, veremos que el globo se hincha, es decir, el volumen que ocupa el gas ha aumentado pero la cantidad de gas que tenemos dentro permanece constante. Además el globo, al poder deformarse, hace que la presión sea todo el rato la misma. Por tanto, la densidad del gas disminuirá y el globo se elevará. Matemáticamente la expresión que explica este fenómeno se conoce como Ley de los Gases Ideales:

ρ= p / T R*

Donde p es la presión del gas, T la temperatura y R*= R / M es la constante de los gases ideales dividida por la masa molecular del gas.

En el océano, la cosa es un poco más complicada. Sabemos que el océano es una mezcla, tendremos por un lado el agua (disolvente) y, por otro, materiales disueltos o sales (soluto). Por ello, la densidad en el océano dependerá también de la cantidad de materiales disueltos que tengamos. Esta propiedad se llama salinidad (S) y mide los gramos de sales que hay en 1 kg de agua oceánica.

Tendremos entonces, que la densidad en el océano va a depender de la salinidad, la temperatura y la presión, de una forma mucho más complicada que en el caso de los gases ideales:

ρ=ρ(S, T, p)

Aunque la expresión analítica de esta ecuación es muy complicada, para nuestro experimento sólo necesitamos saber algunas relaciones sencillas:

- Si la temperatura aumenta, entonces la densidad disminuye.

- Si la salinidad aumenta, la densidad también lo hace.

- Si cambiamos la salinidad y la temperatura no podemos determinar cómo cambiará la densidad. Pero, si bajamos mucho la temperatura y también aumentamos mucho la salinidad, la densidad aumentará y viceversa.

- Ahora bien, si aumentamos mucho la temperatura y también aumentamos mucho la salinidad, al final la temperatura es la que acaba ganando, y por tanto la densidad terminaría disminuyendo.

Estudiemos qué le ocurre a una parcela o burbuja de agua (como si aisláramos un trocito de agua, que va a tener una temperatura y densidad determinada que no va a cambiar), si cambian las características de densidad del agua que la rodea. En nuestro experimento, representaremos esta parcela con un huevo.

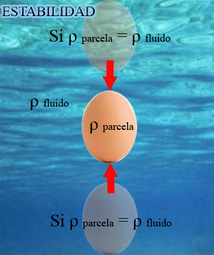

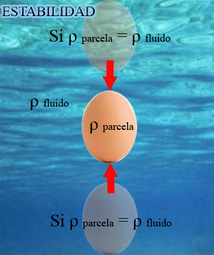

Estabilidad: La parcela será estable si su densidad es igual que la densidad del agua (o fluido) que la rodea. Es decir, la parcela no va a experimentar movimiento, se quedará quieta en la misma posición en la que esté. Además si intentáramos moverla arriba o abajo, la parcela tendería una y otra vez a volver a su posición original.

Inestabilidad: Ocurre cuando la densidad de la parcela es diferente a la densidad del agua que la rodea. La parcela experimentará movimientos que la llevarán a posiciones diferentes de la original (no se quedará quieta). Aunque nosotros intentemos colocarla en su posición original, se moverá todo el rato. Si la densidad del agua es mayor que la densidad de la parcela, ésta tenderá a subir (flotará). Si la densidad del agua es menor, la parcela tenderá a bajar (se hundirá).

Esto se debe al empuje hidrostático, que es la fuerza vertical que un fluido ejerce sobre un cuerpo sumergido en él. La expresión para el empuje es:

E= ρ f g Vc

Donde ρf es la densidad del fluido que rodea al cuerpo, g es la gravedad y Vc es el volumen del cuerpo.

Si aumentamos o disminuimos la densidad del fluido que rodea a la parcela, hacemos que un empuje hidrostático la mueva hacia arriba o hacia abajo.

En este experimento vamos a demostrar estas características de las masas de agua oceánicas. Para realizar el experimento se necesita:

- Dos vasos de tubo largos

- Un huevo

- Agua fría y caliente

- Sal

El huevo representará nuestra parcela de agua, con una temperatura y densidad determinada.

Primero vamos a echar agua fría en uno de los vasos. Veremos que al introducir el huevo, éste se hunde. Es inestable, porque la densidad del huevo es mayor que la densidad del agua, el huevo tiende a hundirse.

Si empezamos a añadir mucha, mucha sal en el recipiente, estaremos aumentando la densidad del agua, siendo la temperatura la misma.

Llegará un momento en el que el huevo comience a ascender. La densidad del agua será mayor que la densidad del huevo.

Sin embargo, si ahora echamos agua caliente, veremos que el huevo vuelve a bajar.

Esto se debe a que, a pesar de haber añadido mucha sal, la temperatura termina ganando a la salinidad, haciendo que la densidad del agua disminuya hasta que es menor que la del huevo. Aunque añadamos más sal todavía, la densidad no aumentará, sino que seguirá siendo menor que la del huevo.

Theoretical basis

Density is a physical property of matter that accounts for the relationship between the mass of a certain substance and its volume.

ρ = m/v

In the world of ideal gases, temperature and density are inversely related. For instance, if we heat up an elastic balloon that contains a certain gas, it will expand. This means that the volume of the balloon increases without loosing mass. Moreover, it is important to remind that since our balloon is elastic, the gas inside the balloon is also free to expand, thus we can consider that pressure remains constant in the process. Therefore, under these conditions, the density of the gas will decrease and the balloon will rise up. The equation that explains this phenomenon results from the ideal gas law:

ρ = P/TR*,

where P and T are the pressure and the temperature of the gas, respectively and R*=R/M is the ideal gas constant.

In the case of the ocean, this relationship becomes more complicated. We do know that ocean water is a mixture which contains not only pure water (solvent) but also salt and other substances (solute). Therefore density of the ocean water will depend on the mass of ocean water solutes as well. Salinity (S) is the physical magnitude that accounts for the mass of solutes that exist in a kg of ocean water. As a consequence, density of ocean water is a function of temperature, salinity and pressure.

ρ = ρ(S, T, p)

Assuming that less dense water floats on top of more dense water, in our experiment, we will address the qualitative effect of temperature and salinity on density:

- Water gets more dense as temperature decreases. So, the colder the water, the more dense it is. Therefore, given two layers of water with the same salinity, the warmer water will float on top of the colder water.

- Water gets more dense as salinity increases. So, the saltier the water, the more dense it is. Therefore, given two layers of water with the same temperature, the fresher water will float on top of the saltier water.

- Because this is a qualitative approach, we won't be able to determine what happens with density when salinity increases as temperature decreases. However, if temperature decreases as salinity increases, water will surely get more dense.

- In addition, we do know that temperature has a greater effect on the density of water than salinity does. So a layer of water with higher salinity could float on top of water with lower salinity as long as the layer with higer salinity is quite a bit warmer than the lower salinity layer.

Let's analyse what happens with a parcel of water or with an object (characterised by a fixed density) which is inmersed in a certain fluid of varying density. In our experiment, the object will be represented as an egg:

Stability: the object will be in equilibrium as long as its density is equal to the density of the surrounding fluid. Under these conditions, the object will neither sink nor rise.

Instability: this situation takes place when the density of the object is different from the density of the surrounding fluid. In the case that the density of the object is greater than the fluid in which it is inmersed, the object will sink. On the contrary, If the density of the object is lower than the fluid in which it is inmersed, it will float.

This phenomenon is due to the bouyancy force (E) which is the vertical force exerted by a certain fluid that opposes the wheight of an inmersed body:

E=ρgV,

where ρ is the density of the fluid in which the object is inmersed, g is the gravity constant and V is the volume of the object.

The bouyancy force will cause the object to move as the density of the surrounding fluid changes.

Experimental design

This experiment aims to describe the properties of different oceanic water masses. To do that, we need:

- 2 glasses

- 1 egg

- Cold and hot water

- Salt

The egg will represent the parcel of water or the object that we were referring to within the theoretical framework. Note that the egg will be characterised by its own temperature and density.

The first step consists on pouring cold water into one of the glasses. The egg will sink under these conditions (instability) since its density is greater than the density of cold water.

If we add salt to the same glass of water (without changing its temperature), we will be increasing the density of the water. At a certain point in which the density of the water is greater than the density of the egg, it will float.

However, if we pour hot water to the same glass, we will see that the egg starts sinking again.

This is due to the fact that hot water contributes to decrease the density of the water. Remember that temperature has a greater effect on the density of water than salinity does.

Temas relacionados:

Créditos:

Belén Rodríguez de Fonseca

Irene Recuerda Gavilán