Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Tornado

- Fundamento

- Diseño

- English version

- english version

1-DEFINICIÓN

El tornado es una columna de aire en rotación, con forma de embudo, que gira de manera muy violenta en la atmósfera (Fig. 1). Los tornados se descuelgan comúnmente desde la base de una nube de tormenta ó cumulonimbus hasta que alcanzan el suelo. Su diámetro oscila desde las decenas de metros hasta varios kilómetros. Debido a los vientos muy intensos que producen, los tornados son capaces de arrancar árboles de cuajo y succionar casas. Los tornados siguen la misma trayectoria que la nube de tormenta, desplazándose a unos 50 km/h.

Fig. 1: Fotografía de un Tornado en la atmósfera. Fuente: www.extremeinstability.com

2-¿QUÉ TIPOS DE NUBES PRODUCEN TORNADOS?

CUMULONIMBUS: Son nubes que se producen por CONVECCIÓN (ver experimento). En primavera/verano, el aire en contacto con el suelo se calienta y comienza a ascender. Durante su ascenso, el vapor de agua condensa y se forman las nubes de tormenta, de aspecto blanco y esponjoso en su parte superior y gris y amenazador en su base.

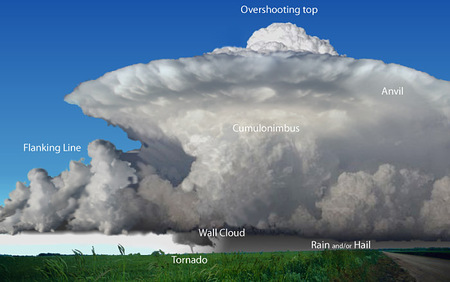

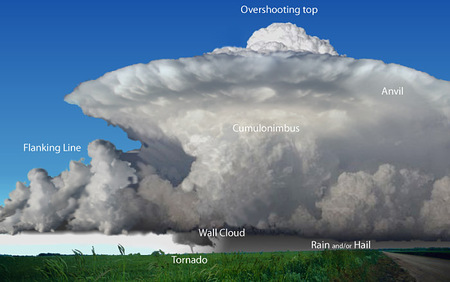

SUPERCÉLULAS TORNÁDICAS: Pertenecen a las nubes de tormenta más intensas. Éstas, presentan un cierto grado de organización, pues las corrientes ascendente y descendentes nunca se encuentran. Además, se puede observar como estas nubes rotan (meso-ciclones). Los tornados se producen en la base de estas nubes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Cumulonimbus: Diferentes partes de una Supercélula tornádica, donde se puede apreciar el tornado en la base de la misma. Fuente: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

3-CLASIFICACIÓN DE TORNADOS EN LA ATMÓSFERA

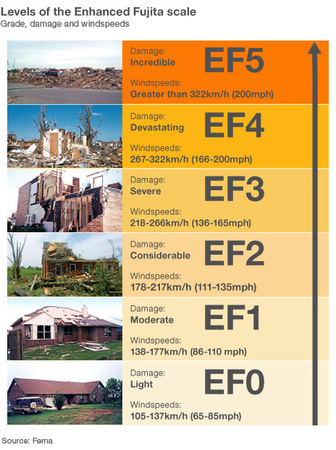

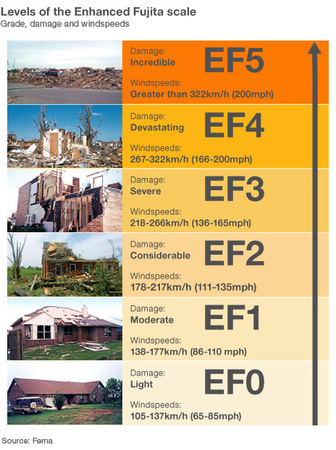

ESCALA MEJORADA DE FUJITA (Fig. 3)

A la hora de clasificar los diferentes tornados que tienen lugar en la atmósfera, se utiliza la Escala Mejorada de Fujita (Fig. 3). Esta escala tiene en cuenta la intensidad del tornado según los daños que produce, el viento en su seno, y su diámetro en la base. Mientras que los tornados más débiles (EF0) producen daños leves en estructuras, los más intensos (EF5) pueden albergar en su seno vientos superiores a 322 km/h.

Fig. 3: Escala Mejorada de Fujita. Fuente: www.fema.gov

4-¿DÓNDE SE PRODUCEN MÁS TORNADOS EN EL MUNDO?

TORNADO ALLEY (CALLEJÓN DE LOS TORNADOS-EE.UU.)

Se conoce coloquialmente como Tornado Alley (Fig. 4) a la región que comprende los estados centrales de EE.UU. (grandes llanuras). Esta región se encuentra entre las Montañas Rocosas y los Montes Apalaches, y sobre ella converge el aire frío/seco de las Montañas Rocosas con el cálido/húmedo del Golfo de México. Esta convergencia de masas de aire de diferentes características favorece el desarrollo de convección profunda y supercélulas tornádicas.

Fig. 4: Número medio de tornados al año en EE.UU. Fuente: Oklahoma Climatological Survey.

In case you are visiting this experiment and you are a not a spanish speaker, we have also prepared an english version in the following video.

1-DEFINITION

A tornado is a violent fast-rotating, funnel shaped, column of air that takes place in the atmosphere (Fig. 1). The tornado typically forms between the cloudbase of a T-storm/Cumulonimbus cloud and the ground, and its diameter can range between meters to several kilometers. Due to the extremely strong winds they often produce, tornadoes are able to uproot trees and destroy entire houses. The direction and movement velocity that a tornado follows is generally given by the steering T-storm cloud motion (~ 50 km/h).

Fig. 1: Picture of a Tornado in the atmosphere. Source: www.extremeinstability.com

2- WHAT TYPE OF CLOUD CAN PRODUCE TORNADOS?

CUMULONIMBUS: These clouds are associated with CONVECTION (see experiment). In spring and summer, the air layer closer to the ground heats up and starts to ascend. During this process, the water vapor in the ascending air parcels condenses and thus T-storm clouds develop. These clouds have a white and spongy appearance on the top and dark and threatening in their base.TORNADIC SUPERCELLS: These are associated with the most intense T-storms due to their high degree of organization. In their interior, the updraft and downdraft currents do not encounter and therefore these storms have a longer lifetime. In addition, these cloulds rotate in the tropospheric mid-levels (mesocyclone) and tornadoes typically form underneath (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Cumulonimbus: Different features of a Tornadic Supercell, with a formed Tornado over the cloudbase. Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

3-TORNADO CLASSIFICATION

ENHANCED FUJITA SCALE (Fig. 3)

The Enhanced Fujita Scale is used in the scientific community to classify different tornado events (Fig. 3). This scale classifies tornadoes based on their associated winds, base diamater and the damage they produce. Whereas the weakest tornadoes (EF0) typically produce light damage on private property, the most intense (EF5) are associated with catastrophic winds even greater than 322 km/h.

Fig. 3: Enhanced Fujita Scale. Source: www.fema.gov

4-WHERE ARE TORNADOES MOST COMMON IN THE WORLD?

TORNADO ALLEY (USA)

So-called Tornado Alley (Fig. 4) is the region that extends along the central states of USA (Great Plains). This area is situated between the Rocky and Appalachian Mountains, where the warm/moist air from the Gulf of Mexico and cold/dry air from the the Rocky Mountains concur. As a consequence, the convergence of air mases of different characteristics favors the occurrence of deep convection and tornadic supercells.

Fig. 4: Average number of Tornadoes per year in the US. Source: Oklahoma Climatological Survey.