Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Efecto Invernadero

- Fundamento

- Experimento 1

- Experimento 2

- english version

- EXPERIMENTO 3

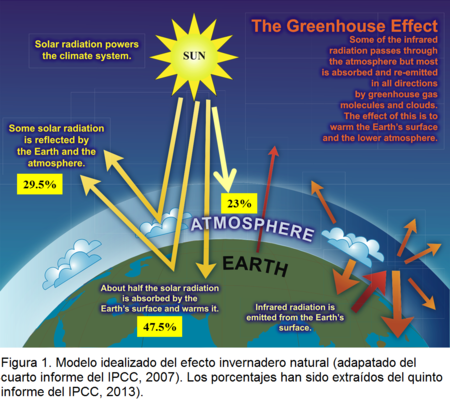

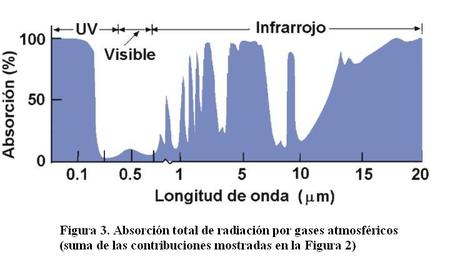

El efecto invernadero es un fenómeno consistente en que la mayor parte de la radiación infrarroja emitida por la superficie terrestre no escapa al espacio exterior del planeta sino que es absorbida y re-emitida en todas las direcciones por ciertos gases atmosféricos y por las nubes. Consecuentemente, esta radiación infrarroja re-emitida desde la atmósfera alcanza la superficie terrestre, siendo absorbida por ésta, por lo que el resultado del efecto invernadero es calentar la superficie terrestre así como la región atmosférica más próxima a ésta última (Fig. 1).

Por tanto, la temperatura global media del planeta es el resultado combinado de su calentamiento por absorción de radiación solar, enfriamiento por emisión de radiación infrarroja y del efecto invernadero, de modo que sin la existencia de éste último la temperatura del aire en superficie sería bastante más baja (del orden de unos -18ºC en su valor medio global).

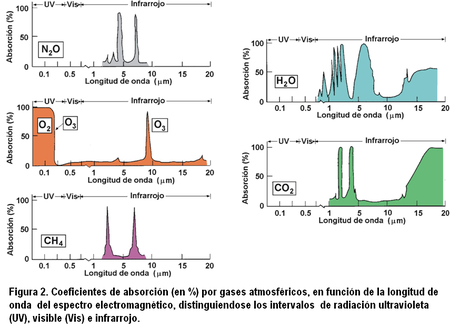

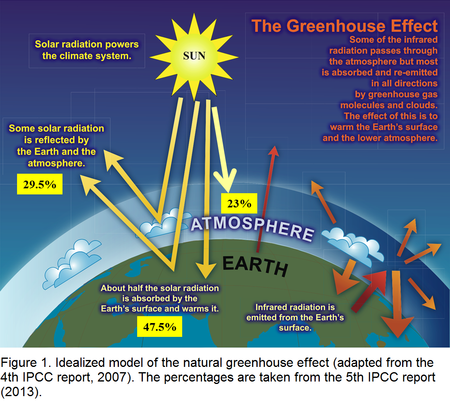

Los gases atmosféricos que intervienen en el efecto invernadero (conocidos como “gases de efecto invernadero”, GEI) son fundamentalmente el vapor de agua (H 2O), el dióxido de carbono ( CO2) , el ozono (O3), el óxido nitroso (N2 O ) y el metano (CH4), junto con otros gases exclusivamente antropogénicos (es decir, producidos por las actividades del ser humano) como son ciertos productos formados por moléculas de carbono y halógenos (por ejemplo, los clorofluorcarbonos, CFCs).

La Figura 2 muestra la absorción selectiva de radiación por parte de gases atmosféricos , de la que se observa que el GEI más importante que contribuye en el efecto invernadero natural (es decir, sin considerar la intervención humana) es el vapor de agua, seguido del dióxido de carbono.

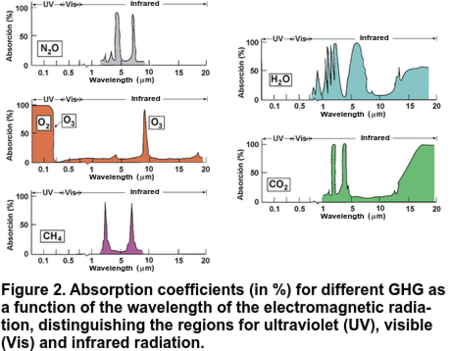

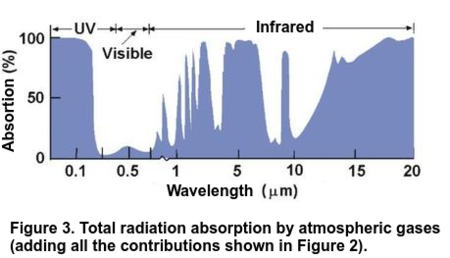

La Figura 3 ilustra el resultado total de la absorción radiativa por la atmósfera terrestre y que determina el efecto invernadero natural, observándose que sólo la radiación de longitud de onda de aproximadamente 7-9 micrometros y 10-12 micrómetros (conocidas como “ventana atmosférica”) escapa al espacio exterior. Como contribución adicional a los GEIs naturales, en general, las nubes absorben en torno a los 11 micrómetros.

Teniendo en cuenta todo lo expuesto, si bien el efecto invernadero natural es fundamental en el clima del planeta evitando que la temperatura media global sea en torno a -18ºC, un aumento de los niveles de los GEIs por parte de las actividades humanas (fundamentalmente de CO2 y GEIs exclusivamente antropogénicos) causaría un aumento del valor medio global de la temperatura en superficie del aire del planeta.

Experimento 1 de Efecto Invernadero

Con este experimento mostramos el efecto invernadero debido a la atmósfera, como se ha explicado en el fundamento teórico.

Material necesario

- 3 termómetros cuyo rango de medida comprenda las temperaturas habituales en la zona del experimento.

- 2 recipientes iguales y algo para cerrarlos (como algodón).

- Un soporte para sujetar el termómetro.

- Cartulina negra.

¿Cómo se hace el experimento?

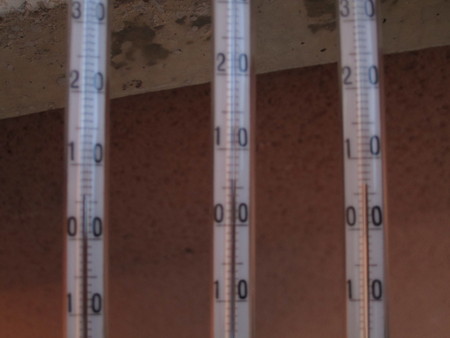

Comprobamos que los tres termómetros tienen la misma temperatura antes de realizar el experimento, ya que si no las medidas podrían ser erróneas. En nuestro caso marcan 6°C.

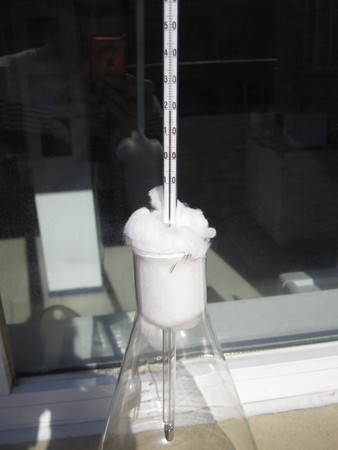

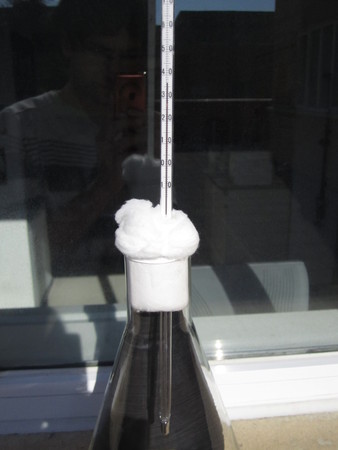

Ahora que tenemos todos los materiales preparados, introducimos un termómetro en cada recipiente y colocamos el tercer termómetro sobre su soporte. Ponemos al sol el conjunto para ver qué ocurre.

Al pasar un tiempo para que se equilibren los termómetros (en nuestro caso 10 minutos), podemos observar que las temperaturas que marcan son distintas.

El termómetro que está expuesto a la radiación solar sin ningún recipiente marca la mínima temperatura. Ha aumentado hasta los 13°C debido a que la radiación solar calienta el bulbo del termómetro. La radiación solar no calienta el aire (excepto en algunos gases muy concretos). Es la radiación de onda larga la que calienta el aire.

El termómetro dentro del recipiente sin cartulina marca la temperatura de 20°C. El cristal deja pasar la radiación solar, que calentará la superficie sobre la que se encuentra (y el termómetro en su interior), por lo que ésta emitirá radiación de onda larga. El cristal absorbe esta radiación, calentándose y emitiendo a su vez radiación de onda larga, lo que producirá un calentamiento del aire en su interior, de forma análoga al efecto de los gases de efecto invernadero en la atmósfera. Por ello, la temperatura es mayor que en el caso del termómetro libre (además, al estar cerrado se impide el transporte de calor por movimientos convectivos).

El tercer termómetro con la cartulina negra tiene la mayor temperatura de los tres, alcanzando temperaturas de hasta 37°C. El motivo es que los materiales de color oscuro absorben mayor cantidad de radiación solar, se calientan más y por tanto emiten radiación de onda larga más energética. Con esta experiencia podemos ver que la magnitud del efecto invernadero también dependerá del tipo de superficie sobre el que incida la radiación solar (una superficie helada o nevada tiende a reflejar buena parte de la radiación solar que le llega, mientras que la superficie del mar tiende a absorber buena parte de ésta, lo que hará que se caliente más); cambios en los usos del suelo, o la disminución de los hielos permanentes de la Tierra también pueden afectar a la magnitud del efecto invernadero global y, por tanto, al clima futuro.

Experimento 2 de Efecto Invernadero

Material necesario

- 3 termómetros, con un rango de m edidas hasta 100 ºC.

- Una lata de conserva grande, vacía.

- Un soporte para los termómetros.

- Un trozo de plástico de forma semicilíndrica.

- Agua hirviendo.

¿Cómo hacer el experimento?

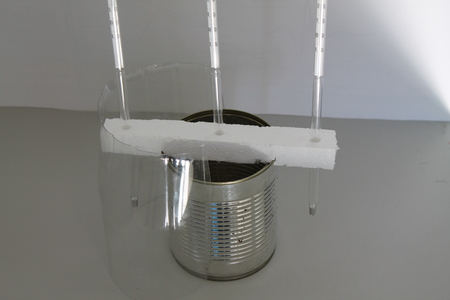

Procedemos a realizar el montaje del experimento como se muestra en la fotografía de abajo:uno de los termómetros medirá la temperatura interior de la lata, y los otros dos se situarán a ambos lados, colocando el trozo de plástico alrededor de uno de éstos, de forma que actuará de forma similar a los gases de efecto invernadero en la atmósfera.

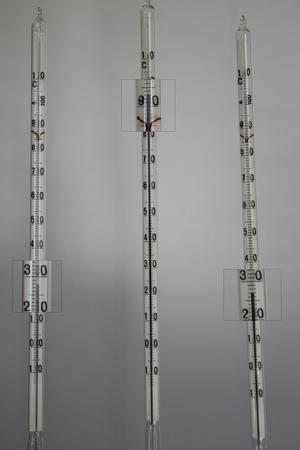

A continuación, nos aseguramos de que los tres termómetros se encuentran en la misma temperatura inicial de equilibrio con el ambiente, que en este caso es de unos 25ºC (fotografía inferior)

Con esta condición inicial de equilibrio, llenamos la lata con agua hirviendo.

Y observamos qué ocurre con cada uno de los termómetros.

Pasado un minuto, se observa que el termómetro central alcanza los 93ºC, mientras el izquierdo marca 28ºC y el de la derecha 27ºC. La diferencia, por tanto, entre ambos es de 1ºC.

Tres minutos después de añadir el agua hirviendo, la situación se muestra en la fotografía de la derecha. En ella, se observa que el termómetro central marca 89ºC, mientras el izquierdo marca 37ºC y el derecho marca 29ºC. La diferencia entre ambos es, ahora, de 8ºC.

Tres minutos después de añadir el agua hirviendo, la situación se muestra en la fotografía de la derecha. En ella, se observa que el termómetro central marca 89ºC, mientras el izquierdo marca 37ºC y el derecho marca 29ºC. La diferencia entre ambos es, ahora, de 8ºC.

Por tanto, podemos concluir que la presencia del plástico aumenta la temperatura del aire en la región que encierra. Esto se debe a que el plástico se calienta al absorber la radiación (de onda larga) emitida por la lata, por lo que también emitirá radiación de onda larga de acuerdo a su temperatura. Ten en cuenta que todas las superficies emiten radiación (a determinadas longitudes de onda), que es directamente proporcional a la cuarta potencia de la temperatura absoluta; es decir, cuanto menor sea la temperatura del cuerpo, mayor será la longitud de onda y menor la energía de la radiación emitida.

En este experimento, la lata caliente representa la superficie de la Tierra (la diferencia es que la superficie de la Tierra se calienta por la radiación solar, mientras que aquí hemos calentado la lata con agua caliente), que es la fuente emisora principal de onda larga. El plástico hace el papel de los gases de efecto invernadero y las nubes en la atmósfera, atrapando y re-emitiendo parte de la radiación de onda larga emitida desde la superficie. La combinación de ambas produce un calentamiento superior del aire en el lado "con atmósfera" (con plástico) respecto del lado "sin atmósfera" (sin plástico).

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND:

Most of the infrared radiation (i.e., longwave radiation) emitted by the Earth's surface is absorbed and reemitted in all directions by certain atmospheric gases and clouds. The re-emited infrared radiation gets back to the Earth's surface, where it is absorbed. Consequently, the effect of this is to warm the Earth's surface and the lower atmosphere, and it is known as the “greenhouse effect”. (Fig.1).

The global mean temperature of the Earth results from the combination of the warming due to the absorption of solar shortwave radiation, the cooling due to the emission of infrared (longwave) radiation and the greenhouse effect. Without the latter, the mean global temperature of the air at the Earth's surface would be much lower than the actual one (it would be approximately -18ºC).

The main atmospheric gases that contribute to the greenhouse effect (known as “greenhouse gases”, GHG) are water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), ozone (O3), nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4). In addition, there are other gases of purely anthropogenic origin which also contribute to the “greenhouse effect”, like those related with carbon and halon molecules (e.g., chlorofluorocarbons).

Figure 2 shows the selective radiation absorption by different atmospheric gases. The water vapor is the GHG that contributes the most to the natural (without consideration of human activities) greenhouse effect, followed by carbon dioxide.

Figure 3 depicts the total radiation absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, which determines the overall natural greenhouse effect. Only the radiation in the bands of wavelength 7 to 9 and 10 to 12 micrometers (known as “atmospheric windows”) can escape the planet. In addition to the natural GHG, clouds also absorb radiation of wavelength close to 11 micrometers.

For all the above, even though the natural greenhouse effect is crucial for the Earth's climate, preventing the mean global surface temperature to decrease down to around -18ºC, an increase in the GHG due to human activities (mainly by increasing CO2 concentrations and by producing GHG of exclusively anthropogenic origin) would cause the mean global Earth's air surface temperature to rise.

EXPERIMENT 1:

This experiment illustrates the greenhouse effect due to the atmosphere, as it is explained in the theoretical background.

Materials:

- 3 thermometers with a thermic range adequate to the environement where the experiment is to be set.

- 2 equal containers and material to cover them, like cotton.

- A basis to support a thermometer.

- Black cardboard

How to do the experiment?

Before performing the experiment we must check that all three thermometers provide the same temperature, or else the measurements could be biased. In our case they indicate 6°C.

Once the material is ready, we place a thermometer in each of the containers and we leave both containers and the spare thermometer under the sun.

After reaching equilibrium (in our case it took 10 minutes), we can observe that the temperatures measured by each thermometer are different.

The thermometer that was left under the sun without any container shows the minimum temperature. Its temperature has risen up to 13ºC due to the Sun's warming of the thermometer's bulb. Solar radiation almost does not warm the air at the lower troposphere, next to the Earth’s surface. The lower troposphere is mainly warmed by the longwave radiation.

The thermometer in the container without the black cardboard shows 20ºC. The glass in the container is simulating the effect of the atmosphere. The longwave radiation stays inside the glass container warming up the air and the exterior thermometer.

The third thermometer, the one with the black cardboard, shows the maximum temperature, reaching 37ºC. This outcome is due to the greater capacity to emit longwave radiation for dark objects than light-coloured ones, which results in an increased warming of the surrounding air.

EXPERIMENT 2:

Materials:

- 3 thermometers with a measuring range up to 100 ºC.

- A large and empty tin can.

- A support for the thermometers.

- A piece of plastic with semi-cylindrical shape.

- Boiling water.

How to do the experiment?

Make the experimental set-up as the Figure 4 shows. One thermometer will measure the inside of the tin can, and the two others will be placed at the sides of the support. Also, place the piece of plastic around one of these thermometers located at the sides of the support.

Figure 4

Check that all three thermometers provide the same temperature, in equilibrium with the environment. In the case illustrated in Figure 5, they indicate around 25ºC.

Figure 5

Next, fill the tin can with boiling water (Figure 6), and observe how the measurement in each thermometer changes.

Figure 6

Figure 7 shows the measurements registered one minute after adding the boiling water in the tin can. The central thermometer shows 93ºC, whereas the thermometer placed on the left (the one with the piece of plastic around) marks 28ºC and the one on the right shows 27ºC. Thus, there is a difference of 1ºC between the thermometers at both sides of the support.

Figure 7

Two minutes later, the temperatures observed in the experiment are: 89ºC, 37ºC and 29ºC in the central, left and right thermometers, respectively (Figure 8). Now, the difference between the two thermometers at both sides of the support is 8ºC.

Figure 8

In this experiment we observe that the presence of the plastic material warms up the air enclosed by this surface. This occurs because the plastic surface emits longwave radiation (according to its new and higher temperature) after having absorbed the longwave radiation emitted from the hot surface of the tin can. Note that all surfaces emit radiation (at certain wavelengths) which is directly proportional to the fourth power of its absolute temperature: the lower the temperature, the longer the wavelength and the weaker the radiative energy emitted.

The plastic surface plays a role similar to that played by the atmosphere in the “greenhouse effect”, since it emits infrared radiation at all directions after having absorbed the infrared radiation emitted by the hot tin can. Consequently, the air surrounding the thermometer close to the plastic surface warms up, as the temperature of this thermometer shows, with values higher than those obtained by the thermometer located on the opposite side of the support. In the experiment, the tin can simulates the Earth’s surface as an emitter of infrared radiation, both surfaces previously warmed up: the former by the boiling water and the latter by the Sun