Taller Virtual de Meteorología y Clima.

Presión atmosférica

- Fundamento

- Huevo en una botella

- Recipientes que no se separan

- Vela que asciende sola

- english version

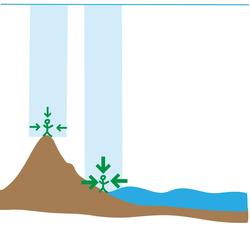

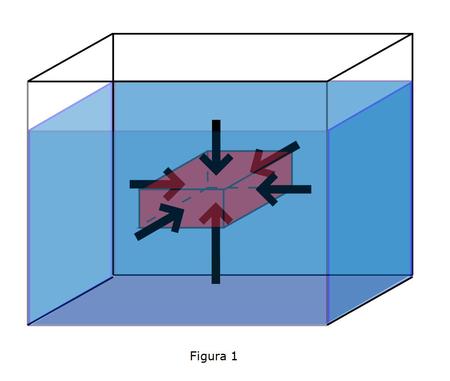

Cuando se sumerge un objeto en un fluido, éste ejerce una fuerza perpendicular a la superficie del objeto (Figura 1). Esta fuerza por unidad de superficie se denomina presión.

Como se ve en la figura las fuerzas horizontales se anulan unas con otras mientras que existe una fuerza neta en la vertical hacia arriba debido a que la presión en la cara inferior es mayor a la superior ya que la presión depende de la altura de fluido que hay por encima.

La atmósfera es un fluido gaseoso que ejerce presión sobre todos objetos inmersos en ella, incluido sobre nosotros.

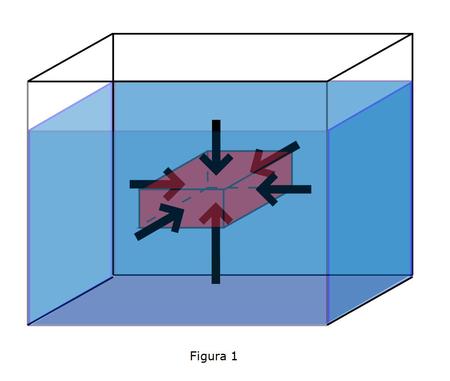

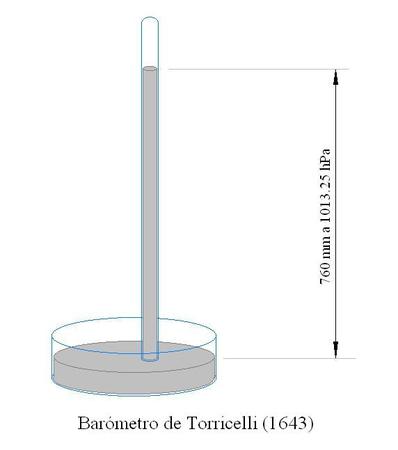

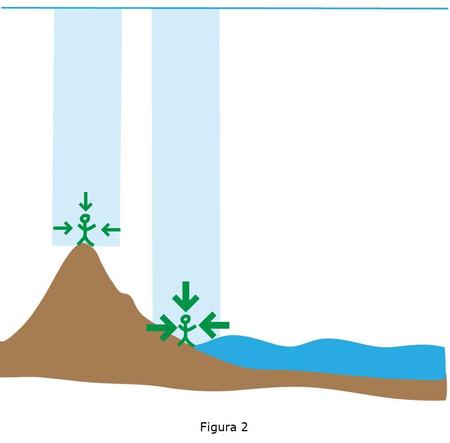

La presión en la atmósfera no es igual en todas partes. Fundamentalmente depende de la altura, siendo más alta cuanto más cerca del nivel del mar nos encontremos. Esto se debe a que la presión atmosférica depende del peso del aire que queda por encima. A mayor altura, menor cantidad de aire queda por encima de nuestras cabezas, que por tanto pesa menos y ejerce menor presión (figura 2). Además como el aire es menos denso según ascendemos en la atmósfera, esto hace que su peso disminuya aún más.

La presión en la atmósfera no es igual en todas partes. Fundamentalmente depende de la altura, siendo más alta cuanto más cerca del nivel del mar nos encontremos. Esto se debe a que la presión atmosférica depende del peso del aire que queda por encima. A mayor altura, menor cantidad de aire queda por encima de nuestras cabezas, que por tanto pesa menos y ejerce menor presión (figura 2). Además como el aire es menos denso según ascendemos en la atmósfera, esto hace que su peso disminuya aún más.

Normalmente no notamos excesivamente la presión atmosférica, pues esta presión también se encuentra en nuestro interior (pulmones, flujo sanguíneo); sí que notamos que se nos taponan los oídos cuando subimos a una montaña o viajamos en avión, ya que la presión atmosférica disminuye. A modo de curiosidad se puede calcular que en promedio al nivel del mar, la masa de la columna de aire atmosférico sobre una superficie de 1 m2 es de unos 10336 kg, es decir algo más de 10 Toneladas.

En realidad, la presión atmosférica no es igual en todos los lugares que se encuentran a una misma altura sobre el nivel del mar; hay zonas en los que por diversos procesos atmosféricos se concentran mas las moléculas de aire y la presión es mayor (Anticiclones) y otras en las que es menor (Ciclones o Borrascas

). La presión en un gas como la atmósfera depende de la temperatura y del volumen del aire, además de la cantidad de gas que tengamos:

En realidad, la presión atmosférica no es igual en todos los lugares que se encuentran a una misma altura sobre el nivel del mar; hay zonas en los que por diversos procesos atmosféricos se concentran mas las moléculas de aire y la presión es mayor (Anticiclones) y otras en las que es menor (Ciclones o Borrascas

). La presión en un gas como la atmósfera depende de la temperatura y del volumen del aire, además de la cantidad de gas que tengamos:

pV=nRT

Donde:

- p = presión

- V = volumen

- n = número de moles del gas

- R = constante de los gases ideales

- T = temperatura

Según la anterior relación (Ley de los Gases Ideales), si aumenta la temperatura de una masa de aire y el volumen se mantiene constante, la presión ha de aumentar. Esto se debe a que el aire está formado por moléculas que se mueven en todas las direcciones; cuando aumentamos la temperatura, estas moléculas se mueven más rápido, chocando contra los objetos y aumentando la presión que ejerce el gas.

En meteorología se suele utilizar más frecuentemente otra forma de la Ley de los Gases Ideales, en función de la densidad del aire (ρ):

p=ρ R’T

donde R’ es el cociente entre la constante anterior R y la masa molecular del aire. De este modo podemos ver que si en la superficie (donde una presión de referencia sería 1013 hPa) se mantiene la presión y la temperatura de la columna de aire que tenemos por encima disminuye, entonces la densidad del aire aumenta. Es decir el aire frío es más denso que el aire cálido (puedes verlo pinchando aquí)

Las diferencias de presión en la atmósfera pueden dar lugar a movimientos de masas de aire, puesto que el aire se mueve de las regiones de presiones más altas a las de presiones más bajas, hasta que la presión se iguala.

HUEVO EN UNA BOTELLA

En este experimento te vamos a mostrar otra forma de ver los efectos de la presión atmosférica y cómo los cambios de presión son capaces de generar movimientos.

Aquí puedes ver el video del experimento:

Cosas que vas a necesitar

Un huevo cocido pelado.

- Un matraz o una botella con la boca ancha, aunque no tan ancha como el huevo que vamos a usar.

- Una cerilla.

- Unas pinzas.

- Un trozo de algodón mojado en un poco de alcohol

- Si tenemos unas pinzas para sujetar la botella mejor, si no hay que tener cuidado para no quemarse.

¿Cómo se hace el experimento?

Se coge el algodón con las pinzas.

Se enciende la cerilla y con ella se enciende el algodón.

Se introduce el algodón en la botella.

Se pone el huevo en la boca de la botella.

¿Qué ha pasado?

El huevo ha entrado en la botella.

¿Por qué ha ocurrido eso?

Recuerda la influencia que tiene la temperatura en el aire: Cuando cambiamos la temperatura el aire se expande (si calentamos) o comprime (si enfriamos), cambiando de volumen o de presión. Al calentar el aire que está dentro de la botella, las moléculas que lo componen han empezado a moverse más rápido. Como la botella está abierta, parte de esas moléculas se han escapado al exterior, manteniendo constante la presión.

Recuerda la influencia que tiene la temperatura en el aire: Cuando cambiamos la temperatura el aire se expande (si calentamos) o comprime (si enfriamos), cambiando de volumen o de presión. Al calentar el aire que está dentro de la botella, las moléculas que lo componen han empezado a moverse más rápido. Como la botella está abierta, parte de esas moléculas se han escapado al exterior, manteniendo constante la presión.

Al poner el huevo en la boca de la botella ya no permitimos que haya intercambio de aire entre el interior y el exterior de la botella. Cuando la llama se apaga (porque se acaba el oxígeno), el aire del interior de la botella comienza a enfriarse otra vez, y sus moléculas empiezan a moverse más despacio. Como el huevo no permite el intercambio de aire, no puede entrar aire dentro de la botella para mantener la presión constante, y la presión en el interior de la botella disminuye.

Ahora la presión que el aire en el exterior de la botella (la presión atmosférica) ejerce sobre el huevo hacia el interior es mayor que la presión que aire del interior de la botella ejerce sobre el huevo hacia el exterior. Debido a esta diferencia de presiones el huevo, que es flexible, se introduce en la botella.

Una vez que está dentro, vuelve a permitirse el intercambio de aire entre el interior y el exterior de la botella y las presiones se igualan.

¿PODREMOS SACAR EL HUEVO DE LA BOTELLA?

Cosas que vas a necesitar

- Un matraz o una botella con la boca ancha, donde previamente hemos introducido un huevo cocido.

- Agua caliente.

- Unas pinzas para sujetar la botella y no quemarnos.

- Un recipiente de plástico.

¿Cómo se hace el experimento?

Con las pinzas, se coge la botella con el huevo dentro y se encaja el huevo en el cuello de la botella.

Se pone la botella encima del recipiente de plástico.

Se echa agua caliente sobre la botella.

Se le da la vuelta a la botella y se espera.

¿Qué ha pasado?

El huevo ha salido de la botella.

¿Por qué ha ocurrido eso?

Al calentar el aire que está dentro de la botella, las moléculas que lo componen han empezado a moverse más rápido. Como la botella está cerrada por el huevo, el aire no puede salir y, por lo tanto, la presión dentro de la botella aumenta.

En este caso, la presión que el aire en el exterior de la botella (la presión atmosférica) ejerce sobre el huevo hacia el interior es menor que la presión que aire del interior de la botella ejerce sobre el huevo hacia el exterior. Debido a esta diferencia de presiones el huevo sale de la botella.

LOS MOVIMIENTOS DEL HUEVO SE PRODUCEN DEBIDO A LOS CAMBIOS DE PRESIÓN DENTRO DE LA BOTELLA.

RECIPIENTES QUE NO SE SEPARAN

En este experimento te vamos a mostrar una forma de ver los efectos de la presión atmosférica. Se trata de un experimento muy fácil de hacer en casa.

Aquí tienes el video del experimento:

Cosas que vas a necesitar

Un trozo de cartulina recortado con la forma del borde de los recipientes.

Una cerilla.

Una pinza.

Un trozo de algodón mojado en un poco de alcohol

Un recipiente con agua.

¿Cómo se hace el experimento?

Se moja la cartulina en agua y se coloca en el borde de uno de los recipientes

Con la cerilla se enciende el algodón, que previamente hemos sujetado con las pinzas para no quemarnos, y se introduce en el recipiente metálico.

Se coloca el otro recipiente sobre el primero de manera que los bordes de los dos recipientes queden bien encajados.

Se espera medio minutito.

Se intenta separar los recipientes.

¿Qué ha pasado?

Los dos recipientes se han quedado pegados el uno al otro y no se pueden separar.

¿Por qué ha ocurrido eso?

Para entender este experimento tenemos primero que entender el efecto que la temperatura tiene sobre el aire: el aire es un gas, por lo que si su temperatura aumenta se expande y si su temperatura disminuye se contrae.

Recordad que la presión atmosférica es la fuerza que ejercen las moléculas de aire en movimiento sobre cualquier superficie. Cuando el aire está caliente las moléculas se mueven más rápido y golpean más veces la superficie. Si calentamos el aire en un recipiente cerrado, este aumento de movimiento hará que aumente la presión del aire sobre las paredes del recipiente. Sin embargo, si el recipiente está abierto, el aire caliente puede escapar hacia el exterior y así mantener constante la presión en el interior.

Al meter el algodón ardiendo en el recipiente, el aire de alrededor se ha calentado, y por tanto se ha expandido. Parte de las moléculas que ocupaban este espacio se han escapado y ahora que está caliente, hay menos cantidad de aire en el recipiente de lo que la que había cuando estaba frío.

Al cerrar el recipiente con el otro, ya no dejamos que haya intercambio de aire entre el interior y el exterior de nuestro recipiente. Para eso es para lo que necesitamos la cartulina mojada, para que haga de aislante y no permita que el aire pase de un lado a otro.

Al esperar un ratito, el aire que está dentro de los recipientes se vuelve a enfriar. Eso se traduce en una disminución de presión, ya que el aire más frío se ha contraído y, como el recipiente está cerrado, no puede entrar aire de fuera para mantener constante la presión.

Eso es lo que ha pasado dentro nuestro experimento: cuando el aire de dentro de los recipientes se ha enfriado, la presión dentro ha disminuido. Hemos creado una diferencia de presión entre el interior y el exterior: la presión atmosférica (exterior) es mayor que la presión en el interior y tiende a “empujar” los recipientes el uno hacia el otro, no permitiendo que se separen con facilidad.

Para separar los recipientes tenemos que hacer una fuerza que supere la presión que el aire de alrededor ejerce sobre los recipientes.

Este experimento casero reproduce el experimento que el alemán Otto Von Guericke (1602-1686) realizó el 8 de mayo de 1654 en Magdeburgo y que es conocido como “Los hemisferios de Magdeburgo”. Von Guericke unió dos hemisferios metálicos por contacto, los cerró herméticamente y después extrajo el aire con una bomba de vacío. Cada hemisferio tenía unas argollas por las que se pasaron unas cuerdas que se ataron a dos grupos de 8 caballos, a los que se hizo tirar de las cuerdas en direcciones opuestas. La fuerza de los 16 caballos no fue suficiente para separar los dos hemisferios metálicos: la presión atmosférica era mayor que la fuerza de los caballos.

Este experimento casero reproduce el experimento que el alemán Otto Von Guericke (1602-1686) realizó el 8 de mayo de 1654 en Magdeburgo y que es conocido como “Los hemisferios de Magdeburgo”. Von Guericke unió dos hemisferios metálicos por contacto, los cerró herméticamente y después extrajo el aire con una bomba de vacío. Cada hemisferio tenía unas argollas por las que se pasaron unas cuerdas que se ataron a dos grupos de 8 caballos, a los que se hizo tirar de las cuerdas en direcciones opuestas. La fuerza de los 16 caballos no fue suficiente para separar los dos hemisferios metálicos: la presión atmosférica era mayor que la fuerza de los caballos.

Vela que asciende sola.

En este experimento vamos a estudiar el efecto de los cambios de temperatura sobre la presión.

Cosas que vas a necesitar.

Un vaso estrecho o probeta, mejor cuanto menor sea su diámetro (que sea similar al de la vela).

- Unas cerillas o un mechero.

- Un vela, que actuará como fuente de calor.

- Un plato o bandeja con agua, mejor cuanto más grande sea.

¿Cómo se hace el experimento?

Colocamos la vela sobre el agua y la encendemos.

Ponemos el vaso o probeta, dado la vuelta, de modo que encierre la vela, intentando evitar que escape aire de su interior.

Esperamos.

¿Qué ha pasado?

Después de un tiempo, el oxígeno en el interior del vaso se consume, y la vela se apaga. Inmediatamente, observamos que el nivel de agua en el interior del vaso se eleva.

¿Por qué ha ocurrido eso?

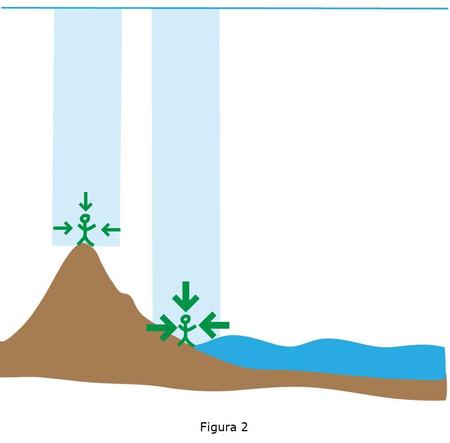

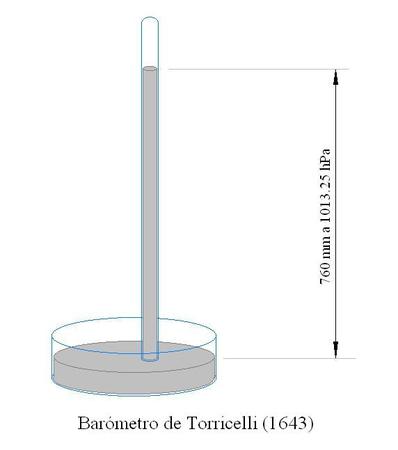

Este efecto de la presión atmosférica sobre los líquidos es el principio de funcionamiento del barómetro que inventó Torricelli en 1643. En este instrumento, un tubo estrecho (como el vaso) se coloca encima de una cubeta, y el líquido usado es el mercurio. Dado que la columna de mercurio en el tubo está en equilibrio para una presión atmosférica de 1013 hPa, cuando la presión varía, lo hace también la altura del líquido en el tubo, por el mismo principio que el que se ha estudiado en este experimento.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND.

When a body is immersed in a fluid, the fluid exerts a force perpendicular to the body's surface (Figure 1). The term pressure refers to this force per unit of area.

As shown in Figure 1, horizontal forces cancel, while there is a net vertical upward force because the pressure at the bottom surface is larger than on the top one, due to the dependence of the fluid pressure on the height above the surface.

The atmosphere is a gaseous fluid that exerts pressure over every object immersed in it, ourselves included.

Atmospheric pressure varies in space and time and is basically dependent on height, being higher close to the sea level, because atmospheric pressure depends on the weight of the air above. The higher the altitude, the smaller the amount of air above, so it will be lighter and atmospheric pressure will be lower (Figure 2). In addition, the decrease in weight is greater because air density decreases with height.

Atmospheric pressure varies in space and time and is basically dependent on height, being higher close to the sea level, because atmospheric pressure depends on the weight of the air above. The higher the altitude, the smaller the amount of air above, so it will be lighter and atmospheric pressure will be lower (Figure 2). In addition, the decrease in weight is greater because air density decreases with height.

We usually do not really notice atmospheric pressure, because it is also inside us (in our lungs, blood flow…); but we do notice the pressure in our inner ear when we climb a mountain or travel by plane, due to the decrease in the atmospheric pressure. As a curiosity, you can do the calculation and check that on average the mass of a 1m2 air column at sea level weights around 10 336 kg, i.e., more than 10 metric tons.

But atmospheric pressure is not only dependent on height, it may also be different in places that are at the same altitude above sea level: different atmospheric processes may lead to the accumulation of more air molecules in some regions (anticyclones) and less in others (cyclones).

The pressure of a gaseous fluid depends not only on the amount of gas molecules, but also on the temperature and the volume of the gas, as it is expressed in the ideal gas equation:

The pressure of a gaseous fluid depends not only on the amount of gas molecules, but also on the temperature and the volume of the gas, as it is expressed in the ideal gas equation:

pV=nRT

Where:

- p = pressure

- V = volume

- n = number of moles of gas.

- R = ideal gas constant

- T = temperature

According to the relation above, if the temperature of an air mass increases and its volume stays constant, then pressure must also increase. This occurs because air molecules move in all directions; as temperature increases, molecules move faster, colliding with objects and increasing the pressure exerted by the gas.

In Meteorology, the ideal gas law usually appears as a function of air density (ρ):

p=ρ R’T

with R’ being the ratio of the ideal gas constant (R) to the air molecular mass. Thus, from this relation we can see that if the temperature decreases at the surface and the pressure does not change, then air density must increase. That is, cold air is denser than warm air (click here to watch it).

Differences of atmospheric pressure are one of the causes of the movements of air masses in the atmosphere, as the air moves from areas of higher pressure to those of a lower pressure in order to balance the pressure gradient.

EGG IN A BOTTLE.

In this experiment we will show a different way of “seeing” the effects of atmospheric pressure and how changes in pressure can generate movements.

You can watch the experiment video here:

Neccesary materials.

- A flask or a wide mouth bottle , although the mouth has to be narrower than the egg you are going to use.

- A match.

- A pair of tweezers.

- A cotton piece soaked in alcohol.

- A pair of tweezers that can hold the bottle (and so not burn your fingers).

How to do the experiment?

How to do the experiment?

Take the cotton piece with the tweezers.

Set the cotton piece on fire with the match.

Introduce the cotton piece in the bottle.

Put the egg in the bottle neck, without pushing it.

What happened?

The egg has got inside the bottle.

Why did this happen?

Remember the effect of temperature in air: When the temperature changes, the air expands (if it is heated up) or compress (if it is cooled down), thus changing either volume or pressure. When you heat the air inside the bottle, air molecules move faster. Since the bottle is open, part of these molecules escape from the bottle, keeping constant pressure.

When you put the egg in the bottle mouth, the exchange of air with the exterior stops. When the flame vanishes (because the oxygen is depleted), the air inside the bottle starts to cool down again, the molecules move slower and, as air exchange is prevented by the egg, the pressure inside the bottle decreases.

Now we have different pressures both inside and outside the bottle, where the atmospheric pressure is still the same. Air outside the bottle exerts a stronger force on the egg than the air inside the bottle, pulling the egg inside the bottle.

Once the egg is in the bottle, the exchange of air with the exterior is possible again and the pressures equilibrate.

COULD WE TAKE OUT THE EGG FROM THE BOTTLE?

Necessary materials.

- A flask or a wide-mouth bottle , where you have introduced a boiled egg

- Hot water.

- A tweezers to hold the bottle without burning your fingers.

- A plastic container.

How to do the experiment?

Grab the bottle with the tweezers and put the egg in the bottle neck.

Put the bottle in the plastic container.

Pour hot water on the bottle.

Wait some seconds.

What happened?

The egg came out the bottle.

Why did this happen?

The hot water warms the air inside the bottle so the air molecules move faster. As the egg is closing the bottle, air cannot go out of the bottle and the pressure inside the bottle increases.

In this case, the pressure of the air outside the bottle (atmospheric pressure) is smaller than the pressure of the air in the interior. Due to this pressure difference, the egg goes out the bottle.

THE EGG MOVEMENTS ARE DUE TO THE CHANGES OF PRESSURE INSIDE THE BOTTLE.

INSEPARABLE BOWLS.

This experiment allows us to see the effects of atmospheric pressure in an easy and simple way.

Here is the video of the experiment:

Necessary materials:

Necessary materials:

- Two identical metallic bowls or similar.

- A piece of cardboard cut with the shape of the bowls-edge.

- A match.

- A pair of tweezers.

- A cotton ball impregnated in alcohol

How to make the experiment?

First, wet the cardboard so that it will make a good juncture between the bowls. Them, place it on the edge of one bowl.

Take the cotton ball with a pair of tweezers and set it on fire with the match. Put down the burning cotton ball into one of the bowls and cover it with the other bowl, trying to match the edges.

Wait around one minute and try to separate the bowls.

What happened?

The two bowls held together and cannot be pulled apart.

Why did this happen?

We need to know the behaviour of gases prior to understand this experiment. Given that air is a gas, it expands when heated and contracts when cooled.

It should be remembered that atmospheric pressure is nothing more than the force exerted by the moving air-particles over the surface. As the air temperature rise up, the particles move faster, increasing the number of impacts on the surface. If air is heated in a closed container, the resulting movement will increase the pressure over its walls. However, were the container opened, warm air would have escaped so as to keep a constant pressure inside it.

When the burning cotton ball is placed into the bowl it heats the surrounding air; warm air inside the bowl expands and part of it escapes. As a result, there are less air particles inside the bowl than were when it was cool. Closing the system with the other bowl (wet cardboard acts as an insulator) prevents the air to flow and equilibrate pressures. After a while, air inside the bowls cools and contracts; in the absence of an inflow, pressure drops inside the system. We created a pressure difference between the inside and the atmospheric pressure outside. Thus, atmospheric pressure is higher and exerts a force on the bowls that prevents their separation. If we want to pull apart the bowls we will need to apply a stronger force than that of the atmospheric pressure.

This home experiment mimics the experiment that the German Otto Von Guericke (1602-1686) performed in Magdeburg on 8 may 1654, generally known as the “Magdeburg Hemispheres”. Von Guericke held together two metallic hemispheres and closed them tightly. Then, he extracted the air inside with a vacuum pump. Each hemisphere was provided with a shackle so that a rope could be attached to it. Two groups of 8 horses pulled the ropes in opposite directions but the hemispheres could not be separated: the force of the atmospheric pressure was stronger than the force of the horses.

This home experiment mimics the experiment that the German Otto Von Guericke (1602-1686) performed in Magdeburg on 8 may 1654, generally known as the “Magdeburg Hemispheres”. Von Guericke held together two metallic hemispheres and closed them tightly. Then, he extracted the air inside with a vacuum pump. Each hemisphere was provided with a shackle so that a rope could be attached to it. Two groups of 8 horses pulled the ropes in opposite directions but the hemispheres could not be separated: the force of the atmospheric pressure was stronger than the force of the horses.

SELF-ASCENDING CANDLE.

In this experiment we will observe the effect of temperature changes on pressure.

Necessary materials.

Necessary materials.

- A narrow glass or graduated cylinder, as narrow as possible (similar in diameter to the candle).

- Some matches or a lighter.

- A candle (the heat source).

- A plate or a tray filled with water, as big as possible.

How to make the experiment?

Put the candle softly on the surface of the water and light it.

Place the glass or the cylinder upside down to enclose the candle; try to prevent the air to escape from the interior of the glass.

Wait.

What happened?

After a while, oxygen inside the glass is consumed and the candle turns off. Just after that, water level rises inside the glass.

Why did this happen?

This effect of atmospheric pressure on liquids is the working principle of the barometer invented by Torricelli in 1643. It consists on a narrow glass tube, closed in its upper edge and placed over a tray filled with mercury. If the column is disposed as to be in equilibrium with an atmospheric pressure of 1013hPa, then any change in atmospheric pressure will vary the height of the column by the same reason as in our experiment.

Temas relacionados:

Créditos:

Elaborado por:

Carlos Yagüe Anguís

Proyecto de Innovación y Mejora de la Calidad Docente. Laboratorio Virtual de Meteorología y Clima (122PCD1144)

IP: Belén Rodríguez de Fonseca